Cross-posting the following article written by Professor Min-Ah Cho and published by the Catholic Institute of Northeast Asia Peace (source)

Multicultural, Multi-ethnic Society and Minjok

Min-Ah Cho, PhD

Assistant Teaching Professor, Georgetown University

For the Korean diaspora, living scattered across the world, the concept of minjok (민족, a Korean term which can mean nation, people or ethnicity, but is often used to denote a single-bloodline or single-ethnic nation) is not intuitive. The same goes for me, who spends most of the year living outside of Korea. Korean students in my classes include international students, second or third generation immigrants to the USA, and children from multi-ethnic families. It is not easy for them to grasp the homogeneity of Korean minjok in terms of blood, emotions, language, culture, and geography. Each of them also conceptualizes their Korean identity slightly differently. If we insist on identifying and emphasizing Korean minjok based on a few conditions such as skin color or language, we risk alienating them. In fact, as much as they face discrimination and pain as minorities living in a white-centered society, they are often also hurt by criticism when visiting Korea or from first generation Korean emigrants for “not being Korean enough.”

Similar to the students I encounter, the experiences of many other Koreans in the diaspora raise questions about the minjok category, which presupposes a homogeneous community. At the same time, the diaspora reminds us that we need to pay more attention and care to the blurred line between Koreans and non-Koreans. There are scars of discrimination marring the experiences and histories of diasporic Koreans, whose position is constantly redefined in our turbulent, changing society through the violence of excluding those considered outside the borders of the “single-ethnic nation.” If we look deeply and reflect upon the lives of diasporic Koreans, whose treasured identity exists in a liminal space, we will be able to break free from a rigid understanding of ethnicity and develop a vivid imagination for designing a shared future with diverse beings. Such imagination is needed today in South Korean society.

The belief that Korea is a single-ethnic nation is nothing more than ideology or myth. There is longstanding academic recognition that, from ancient to modern times, various ethnic groups have united and fought to carve out their own destiny on the Korean Peninsula. Nevertheless, the myth of Korea being a single-ethnic nation is constantly regurgitated in public education, public discourse, and the media. Not only does this belief in a single-bloodline act as a centripetal force to reign in national and communal consciousness in South Korea, but it also gives a sense of legitimacy and inevitability to the political unification of North and South. However, despite being part of a “community of shared destiny” (운명공동체), South Korean society still perceives North Koreans and ethnic-Korean Chinese in ways that discriminate against them and exclude them. Let’s look at the case of North Korean defectors who have come to South Korea, the land of their “compatriots,” after the division and the Cold War. Most either fail to settle down in South Korean society or only just manage to eek out a living in the lowest socioeconomic class, due to the psychological pain and conflict they experience assimilating into South Korean society. Ethnic-Korean people born in China, commonly called Joseonjok, face even more serious challenges. Regarded as economic migrants and stigmatized as potential criminals by South Korean society, they move from one undesirable job to another. In South Korea this June, a fire caused by illegal disregard of occupational safety regulations at the Aricell lithium battery factory killed 31 people, 80% of whom were ethnic-Korean Chinese laborers. In this way, despite sharing skin color and a common language, North Korean defectors and ethnic-Korean Chinese in South Korea are regarded as essentially different.

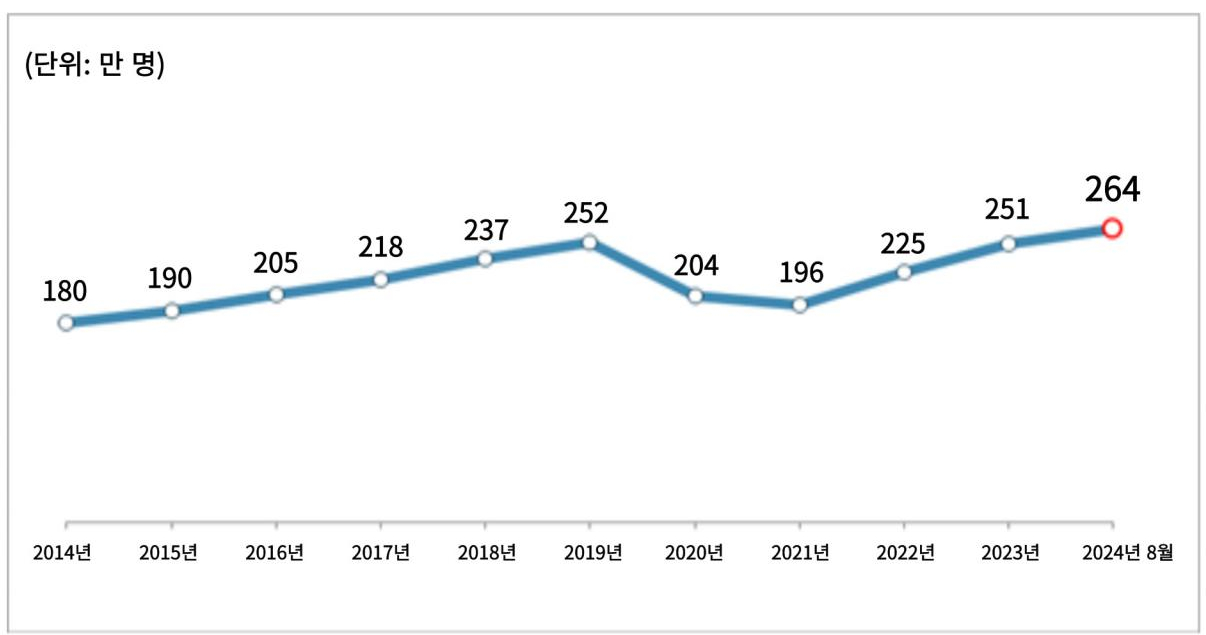

If even so-called “compatriots” (동포, 同胞) who share the same bloodline are treated so callously, what about foreign migrants who do not share the same skin color, language, or culture? According to the Immigration and Foreign Policy Statistical Bulletin released by South Korea’s Ministry of Justice in December 2023, there were 2,575,084 foreigners in South Korea last year, equivalent to 4.89% of the total population. South Korea has begun the transition toward a multicultural and multiethnic society, begging the question, “Is Korean society ready to coexist with people of different ethnicities?” What will the future of the Korean Peninsula look like as a multicultural and multiethnic society, not only with the residents of the North and South, but also with foreign migrants?

South Korea is already a deeply racist society with a clear racial hierarchy. South Koreans are condescending and patronizing toward people of color, including Black people, while being tolerant and friendly toward Whites. But, racism is not a new phenomenon in the Korean context. It has deep and varied roots, including hierarchical Confucian values, admiration of “advanced” Western civilization since the start of the modern era, anti-Black prejudice introduced by the U.S. military since the start of the Korean War, religious influences from White European Christian missionaries, and deepening ties with the United States through the development of capitalism. Since the 1990s, discrimination and violence have become increasingly prominent in the relationship between foreign laborers in South Korea and the indigenous population.

Immigration policies and social attitudes that emphasize inclusion, integration, and “Koreanization” while still drawing strong boundaries between “us” and “them” further darken the future of South Korea as a multi-ethnic society. Laws and institutions created for the convenience of Korean society without understanding migrants’ cultures, histories, and realities only reinforce discrimination. In this legal context, corporations buy migrant workers’ labor cheaply to increase their profits. This exploitative system cements mass discrimination that keeps non-minjok workers at the bottom of the food chain and out of the spotlight. Some businesses use various forms of coercion (threats, violence, deception) and abuse of power to prevent such migrant workers from leaving the workplace, which is akin to modern-day slavery. At the same time, society accepts a strange, discriminatory mindset that it is “natural” not to pay fair wages for labor or to disqualify people from enjoying universal rights simply because they are not “our people” (woori minjok, 우리 민족). Remember that in practice, South Korean society’s narrow definition of “our people” excludes not only migrants from foreign countries but also ethnically Korean people from North Korea and China. In this way, woori minjok, a term intended to unify Korean society for reconciliation and coexistence, simultaneously wields a blade of exclusion and separation.

It is possible that the stories of migrants to South Korea may reveal a darker future than the one we like to imagine when considering coexistence between South and North Korea. This is because in a shared future with North Korea we will encounter many differences in language, culture, and politics. Unless we abandon the illusion of a homogeneous community, where only the chosen can feel safe, and unless we confront the structural forms of discrimination experienced by migrants to South Korea, coexistence and harmony between North and South will remain little more than a romantic or nostalgic idea. The stories of ethnic-Koreans from the North and foreign migrants living along the margins of South Korean society must be told. Their experiences should be an important resource as we envision the future of the Korean peninsula.

After ascending to the papacy in 2013, Pope Francis chose Italy’s southernmost island of Lampedusa for his first trip outside of Rome. The island has become home to tens of thousands of refugees seeking asylum in Europe in the aftermath of political unrest and civil war in North Africa. As European nations refuse to welcome them and with nowhere else to go, they continue to suffer through life in a refugee camp. In his homily among the refugees in Lampedusa, Pope Francis said, “We are a society which has forgotten how to weep, how to experience compassion – ‘suffering with’ others: the globalization of indifference has taken from us the ability to weep!” (Source: Vatican, 8 July 2013, Visit to Lampedusa — Holy Mass) This message is not just an appeal to Christians. It is human nature to feel pain and responsibility in response to the suffering of others uprooted from their homes, experiencing ostracization and discrimination. Rather than upholding stringent conditions and qualifications for “our people,” the future of North and South Korean coexistence should be a society in which all people are respected by virtue of their life and humanity.

Leave a comment